For we did not follow cleverly devised stories when we told you about the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ in power, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty. He received honor and glory from God the Father when the voice came to him from the Majestic Glory, saying, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.” We ourselves heard this voice that came from heaven when we were with him on the sacred mountain. (2 Peter 1:16-18)

The event that took place on this unnamed mountain was earth-shattering. This event, and the words “This is My Son”, resulted in the teaching in 2 Peter. This teaching regarding Jesus was not imagined or deduced, nor had it been fabricated by the apostles. It was a doctrine that had been obtained by living together with Jesus, and affirmed by the proclamation of the Father. These words and the story of Transfiguration are found in all the synoptic Gospels. They are especially important in that they appear in the approximate center of every Gospel, along with Peter’s confession of Jesus’ Messiahship.

What was so significant about this particular incident? Of everything the disciples had experienced with Jesus in the three years they had spent with him, what made this event one of the culminating points of the apostles’ theology? To unravel this, one needs to delve a bit further into the background of the text and the culture at that time.

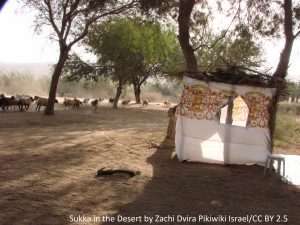

This mountain-top event is sometimes theorized to have taken place during the Feast of Tabernacles, Sukkot. It occurs either 6 days (according to Matthew and Mark) or 8 days (according to Luke) after another meaningful occurrence: the first time Jesus spoke to his disciples about his death. If the assumed relation to the Feast of Tabernacles is correct, Jesus’ first announcement of his coming death could have occurred on the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur. On this day, a goat would have been sacrificed in the Temple of Jerusalem for the atonement of the people of Israel, while another one would have carried their sins to the desert. The coming death of Jesus would be the final atoning sacrifice.

God instructed the people of Israel to commemorate the Feast of Tabernacles in order to remind them of his unceasing provision and protection in the desert after the Exodus. The darker parts of the journey in the wilderness were not mentioned here, only the saving acts of God. This was also the time, every seventh year, when the Sinaitic Covenant was read to the people (the sabbath year or “shmita”, Deut. 31:9-13). In later rabbinical tradition, this developed into a yearly celebration of Simchat Torah, when the yearly cycle of Torah-reading ended and a new one began.

By time of the Feast of Tabernacles, the autumn harvest had been gathered and the great gifts of God celebrated. Symbolically, this autumnal harvesting of fruits points to the final judgment. In this vein, the feast of Tabernacles reflects the celebration after the judgment, when evil has finally been condemned, and salvation and true peace have become reality. Other nations also share in God’s future plans, their remnants being invited to celebrate in his salvation together with the remnant of the people of Israel, at the Feast of Tabernacles (Zech. 14:16).

While the Feast of Tabernacles cannot definitively be determined to be part of the context of the Transfiguration, there are visible hints in the text: the aforementioned timing, Jesus’ words relating to his death and Peter’s offer to build booths. Also, assuming this to be the case, it helps to understand the impact this event had on the three apostles, Peter, James and John, who were led up on the mountain by their master.

What the three apostles saw on the mountain was something completely unexpected and astounding. And yet, it was something that – were it to occur at all – would likely happen during this precise feast. Moses and Elijah appeared in divine glory, together with their master, Jesus. Moses, the embodiment of the Torah; and Elijah, the great prophet who was to come before the Messiah. And now their master was elevated to this group! Jesus was the prophet like Moses, and the presence of Elijah affirmed that he was the Messiah. The apostles had already begun to understand this, but now it had been confirmed, and they had the great honor of witnessing this event. The fulfillment of prophecy and of their dreams were before them: the Torah, the Prophets and the Messiah. For a Jew living in a first-century Middle East, it would have been hard to imagine a moment more glorious than this.

Into this enthralling scene came the voice of God Almighty. Shocking as it must have been in itself, even more striking was the content. The divine voice did not even mention these great heroes of the faith, Moses and Elijah. Rather, it referred to the man they had been following for some time now. Their master was not elevated to the same rank as Moses and Elijah, as it had first appeared; he was elevated beyond them. He alone was the beloved Son of God. With him alone the Father was well pleased. Afterwards, Moses and Elijah disappeared, and the master of these three apostles was again alone with them.

Two thousand years later, lacking a first-century Jewish mindset, it’s difficult to grasp the earth-shattering significance of this moment. These three apostles’ entire beings had been shaken. The Torah and the Prophets were the cornerstones of the Jewish faith. The messiah was supposed to be the awaited continuation of this divine plan. But certainly not above all the rest… not greater than Moses… not greater than Elijah.

Now all their assumptions had been crushed. The entirety of the Torah, Prophets, revelations and great acts of God pointed to this one man. This man was the aim and purpose of everything that God had done before. Their master was the Messiah, Son of God, and besides him there was, is, and will be no one else. Everything and everyone is subjected to him. It is all about Jesus, the beloved Son of God, with whom the Father is well pleased.

Terho Kanervikkoaho, Project Coordinator